The road less travelled

Priscilla Leung on her rule of law mission

16 July 2025

It was in the 1980s when Priscilla Leung Mei-fun first saw foreign ways close up. As a CUHK exchange student in the United States, she was gripped by a culture shock that had the effect of kindling her bond with China.

“Some say, there are people who become more patriotic after going abroad. I’m definitely one of them,” says Professor Leung, now a lawmaker, legal scholar and, most recently, newly named Honorary Fellow of CUHK.

“Soon after arrival in the US, I had issues with identity: Whenever I had to give a speech as an exchange student, I was expected to talk about China. China had just gone through the Cultural Revolution and a lot of other things. But I just knew too little to talk about it,” she readily admits to CUHK in Focus.

Professor Leung was born into a grassroots family in a Tsuen Wan public housing estate. She studied hard enough to earn a place at St Paul’s Co-educational College, an elite school. A brief stay with relatives in Guangdong province for medical treatment in her childhood, while sparking emotional ties, was her only encounter with China then.

The exchange visit to Dickinson College in the US was the turning point. The young Leung had the chance to observe the 1984 presidential election, learning about the electoral system and campaign strategies on site; during holidays, she stayed with American families in different states, gaining insights into the lives of people from various backgrounds.

“After returning from the US, I felt that I must visit Beijing someday,” she says. Back in CUHK with fresh perspectives and a critical mind, she swiftly changed her major to Government and Public Administration and took up presidency of the United College Student Union, adding to her budding portfolio in student affairs after a year in the deputy editor’s chair at CUHK Student Magazine.

As a young student leader, Professor Leung was already displaying the firmness of conviction that is now a trademark of her advocacy in Hong Kong politics. For example, she was dismissive of the “four tsai” ideology to which many of her peers aspired: to have a flat, a car, a wife and babies. She often led discussions about worshipping the materialistic way of life and rejected the trend of pursuing luxury fashion brands.

Her dream of seeing China up front came true after her undergraduate studies. Encouraged by Professor Chang Chak-yan, she took the bold step of accepting an offer from Renmin University of China to study a master’s degree in law – an unconventional choice among her peers – and let go of academic opportunities in France and the US.

“My experience told me that one could not understand China by learning in an air-conditioned room,” Professor Leung says. “In the US, I realised the importance of the rule of law to society, and it became my aspiration to help that take root in China. I also believe in the Chinese saying that ‘reading thousands of books cannot match up to travelling thousands of miles’; this is my outlook on life.”

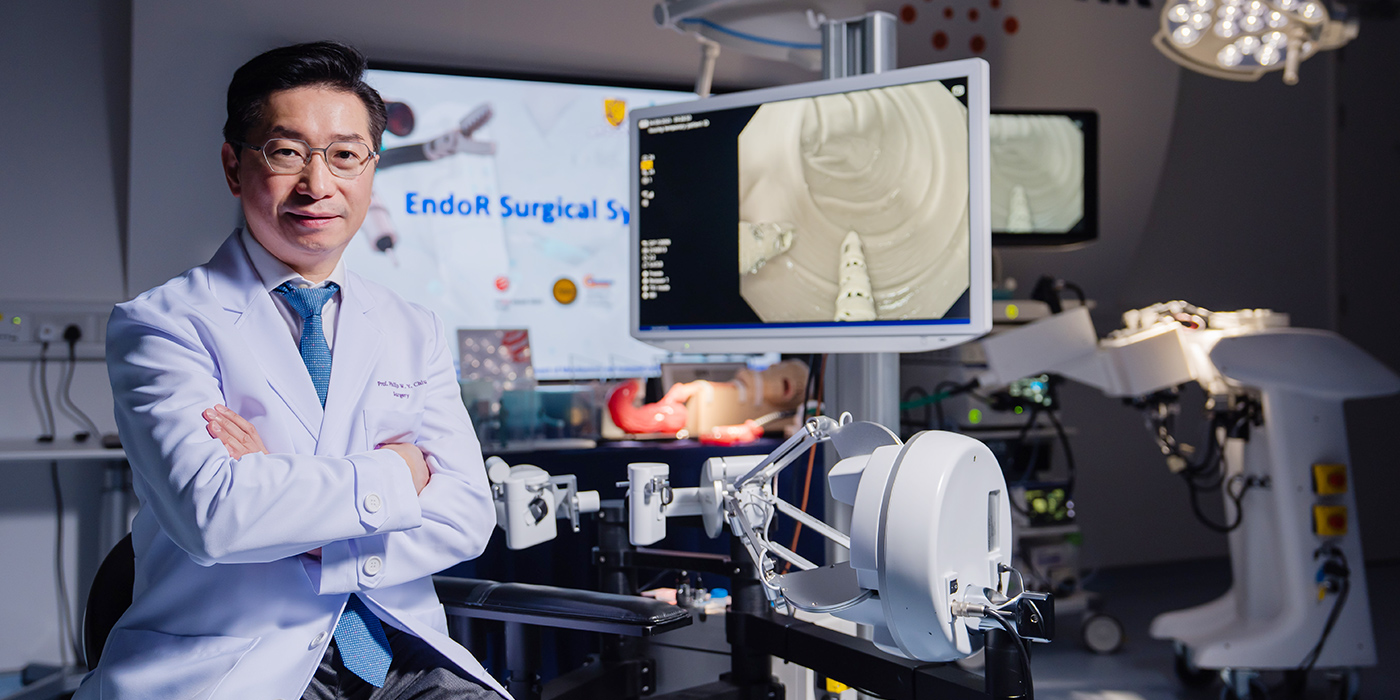

In Beijing, she witnessed poverty and had a taste of it herself, having access to shower water in the university dormitory only once a week. She made up her mind that a legal scholarship was how she could contribute to the rule of law. Not long after joining the City University of Hong Kong as assistant law lecturer, she proposed an idea to her Beijing law school: to publish Chinese case law similar to the format of common law and translate it into English, so as to help the outside world make sense of China’s judicial system.

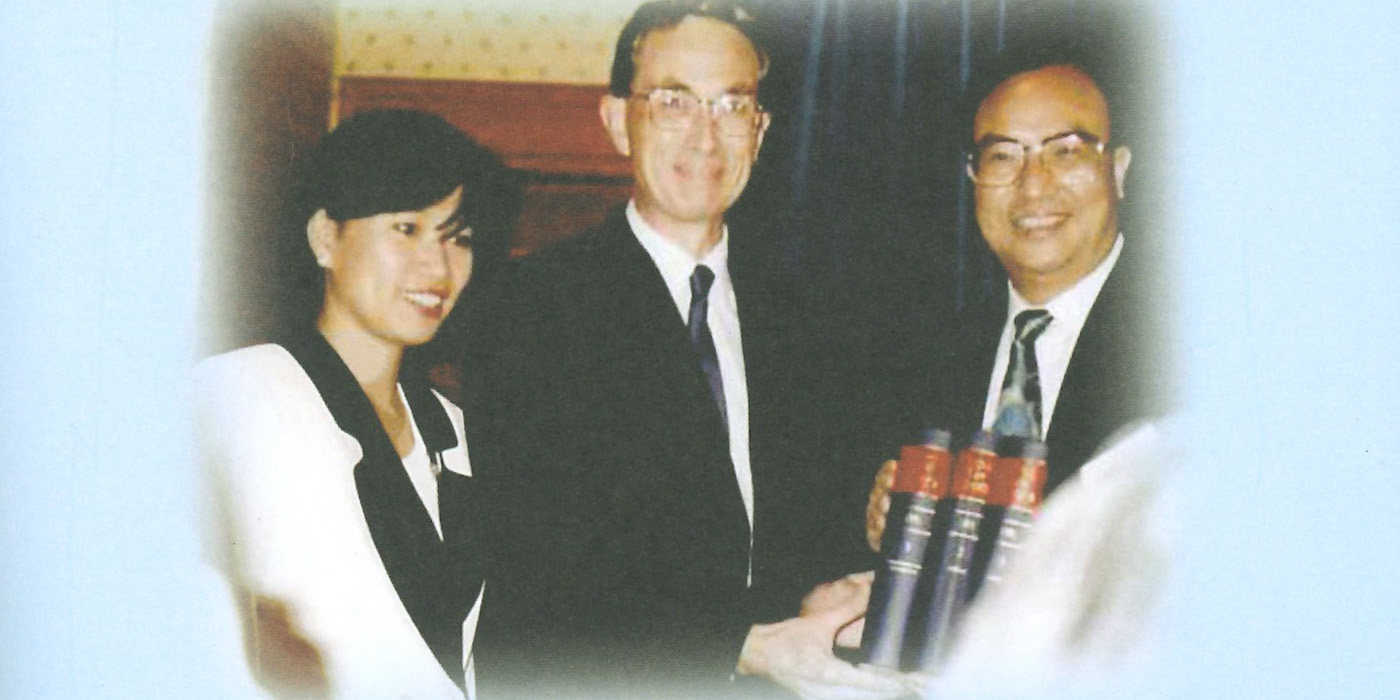

She pitched her suggestion to Professor Zeng Xianyi, the new law dean of Renmin University, who was to become her PhD supervisor later. “I told him that my students were saying, ‘There’s no law in China because they can find no case to study’. He took my idea and convinced the president of the Supreme People’s Court to give the project the green light.” So Professor Zeng was the editor of the Chinese edition, which included court judgments on select areas, and he tasked the young scholar Leung to take charge of the English translation.

For this monumental project, Professor Leung exhausted her network and assembled a team of volunteers made of Hong Kong’s top lawyers, who would help her review the work done by the translation team she recruited.

As a young scholar who needed to earn a living, she had to sell her flat to finance the project, the first draft of which had already cost HK$2 million. Donations were not enough to support it.

The first English edition of China Law Reports was published in 1995. The reports helped the world understand how the Chinese judicial system worked in practice, and the progress of legal reform in the country. They also promoted legal research, legal education and the training of legal personnel.

Professor Leung went on to work as editor-in-chief of Selected Edition of China Law Reports 1991-2004, which focused on additional court judgments concerning economic issues, intellectual property, real estate and cases involving foreign investors. The volumes were similarly seen as valuable resources locally and overseas.

“I believe my story illustrates one point: Opportunities are meant for those who are prepared. When they arise, you must seize them,” she notes.

Her passion continued: In 2008, she ran for the Legislative Council, a role in public service she has held ever since. She was appointed a member of the Hong Kong Basic Law Committee of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) in 2018.

Professor Leung has distinguished herself by helping the local community understand aspects of Chinese legislation relevant to their concerns. She has researched on the laws of marriage, inheritance, adoption and intellectual property of the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, aiming to help resolve legal cases involving the three regions. Shortly after China announced the Belt and Road Initiative in 2016, Professor Leung helped establish the International Academy of the Belt and Road to raise understanding of the laws of countries in the region and facilitate the setting up of dispute resolution mechanisms.

Looking to the future, Professor Leung believes that Hong Kong should recognise its strengths and contribute to national development. This includes participating in Belt and Road projects in construction and financing, seizing opportunities in the Greater Bay Area to drive the development of Hong Kong’s high-tech economy, leveraging the city’s status as an international financial centre to promote financial technology, serving as a bridge between the mainland legal system and common law, and cultivating bilingual talent in Chinese and English.

Beyond governmental level, Professor Leung believes there is work to be done in “people-to-people diplomacy”. That drove her to establish the Hong Kong Association for External Friendship recently to promote exchanges between Hong Kong and the international community, fostering mutual understanding and allowing the world to better understand the city’s current situation.

“Our unique cultural advantages still exist. We need to actively invite friends from abroad and work together to discuss and solve Hong Kong’s problems,” she says.

By Joyce Ng

Photos by Steven Yan